• 特约评述 •

合成生物学助力突破免疫治疗局限性

王子恒1,2, 刘子怡2, 马毓谦1,2, 秦鸿雁2, 赵俊龙2, 张向前1

- 1.延安大学生命科学学院,陕西,延安 716000

2.第四军医大学基础医学院医学遗传与发育生物学教研室,陕西,西安 710000

-

收稿日期:2025-07-21修回日期:2025-10-28出版日期:2025-11-07 -

通讯作者:张向前 -

作者简介:王子恒 (1998—),男,硕士研究生。研究方向为合成生物学和免疫细胞治疗。 E-mail:1355985130@qq.com张向前 (1973—),男,教授,硕士生导师。研究方向为植物天然产物及miRNA调控机制方面的研究和学科教学(生物)领域的教学研究。 E-mail: zxq@yau.edu.cn -

基金资助:国家自然科学基金(82373270);陕西省自然科学基金(2024SF-ZDCYL-03-28)

Synthetic biology empowers breakthroughs in addressing immunotherapy limitations

WANG Ziheng1,2, LIU Ziyi2, MA Yuqian1,2, QIN Hongyan2, ZHAO Junlong2, ZHANG Xiangqian1

- 1.School of Life Sciences,Yan’an University,Yan’an 716000,Shannxi,China

2.Department of Medical Genetics and Developmental Biology,School of Basic Medical Sciences,Fourth Military Medical University,Xi’an 710000,Shannxi,China

-

Received:2025-07-21Revised:2025-10-28Online:2025-11-07 -

Contact:ZHANG Xiangqian

摘要:

免疫治疗近年来在肿瘤、感染性疾病和自身免疫病等领域取得了突破性进展,但其临床应用仍面临信号识别特异性不足、免疫反应调控不精准及毒副作用显著等挑战。合成生物学作为一门新兴的工程化学科,通过模块化设计和基因回路编程,为免疫治疗的精准化改造提供了创新解决方案。本文系统综述了合成生物学在免疫治疗中的关键技术、应用案例及未来方向,旨在为免疫治疗的工程化设计提供理论依据和技术参考。在信号输入环节,工程化受体(如Syn-Notch、RASSL)通过逻辑门控设计(如“与”门)增强靶向性,减少脱靶效应;在信号处理环节,人工基因回路(如CHOMP、SPOC)将病理信号转化为治疗性输出,实现选择性杀伤或动态调控;在信号输出环节,反馈系统和振荡回路(如负反馈抑制T细胞过度活化)优化免疫反应强度与时长,提升安全性。此外,合成生物学技术已成功应用于CAR-T、CAR-NK等细胞疗法,通过受体改造、回路重编程等手段,显著提高了疗效并降低了毒性。未来,随着基因编辑、动态调控等技术的进一步发展,合成生物学驱动的免疫治疗将推动精准医学的实现,为复杂疾病的治疗提供更高效、更安全的策略。

中图分类号:

引用本文

王子恒, 刘子怡, 马毓谦, 秦鸿雁, 赵俊龙, 张向前. 合成生物学助力突破免疫治疗局限性[J]. 合成生物学, DOI: 10.12211/2096-8280.2025-074.

WANG Ziheng, LIU Ziyi, MA Yuqian, QIN Hongyan, ZHAO Junlong, ZHANG Xiangqian. Synthetic biology empowers breakthroughs in addressing immunotherapy limitations[J]. Synthetic Biology Journal, DOI: 10.12211/2096-8280.2025-074.

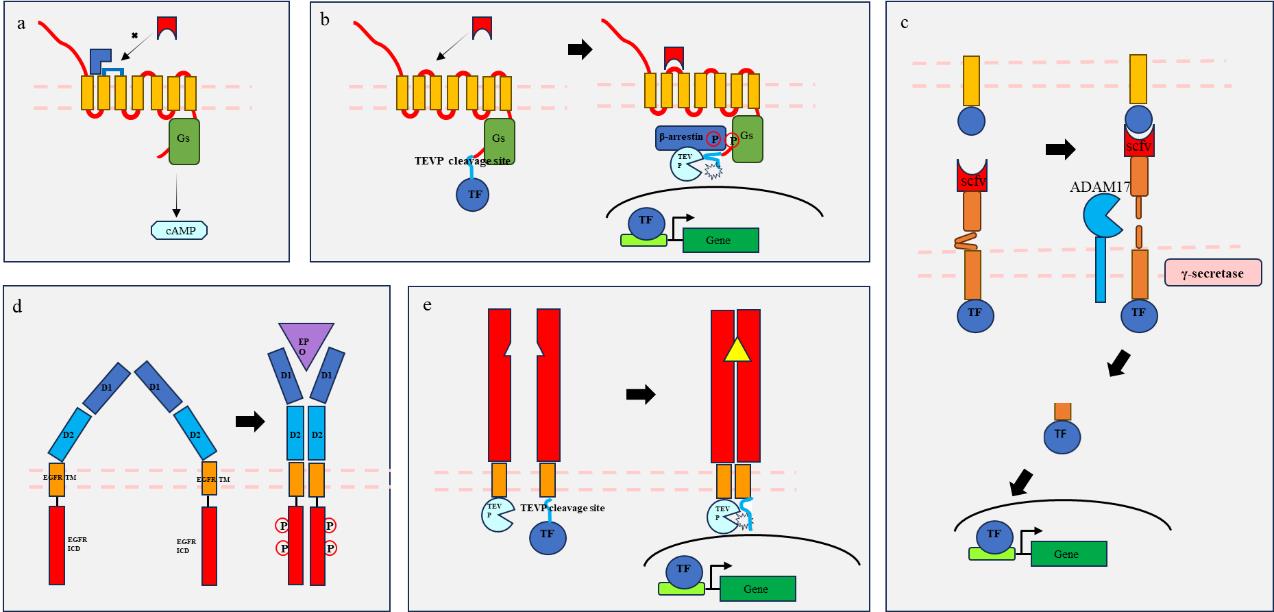

图1 工程化受体原理示意图(a) “RASSL”系统利用GPCR突变使得仅识别特定信号(蓝色)如小分子药物;(b)“Tango”系统利用β-arrestin与磷酸化GPCR空间位置的靠近启动蛋白酶切割释放转TF;(c) “Syn-Notch”系统利用notch受体激活的两次切割(胞外段ADAM17切割,近膜端γ-secretase切割)实现TF释放;(d)“GEMS”系统利用EPOR受体信号传导特点传递可编辑信号(胞外段及胞内段信号改构);(e)”MESA”系统利用受体二聚化空间位置靠近启动蛋白酶切割释放TF。

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of engineering receptor principle(a) The RASSL system utilizes GPCR mutations to recognize only specific signals (blue) such as small molecule drugs; (b) The "Tango" system utilizes the proximity of β-arrestin and phosphorylated GPCR spatial positions to initiate protease cleavage and release of TF; (c) the "Syn-Notch" system utilizes two cleavage processes activated by notch receptors (extracellular ADAM17 cleavage and proximal γ-secretase cleavage) to achieve TF release; (d) The GEMS system utilizes the signaling characteristics of EPOR receptors to transmit editable signals (extracellular and intracellular signal remodeling); (e) The "MESA" system utilizes receptor dimerization spatial proximity to initiate protease cleavage and release of TF.

| 工程化受体 | 优点 | 缺点 |

|---|---|---|

| RASSL[ | 1.GPCR种类繁多且可接受多种配体激活 2.改造GPCR结合配体特异性高 | 1. 依赖于突变 2. 受限于GPCR的配体种类 3. 局限于GPCR自身激活的通路 |

| Tango[ | 1.GPCR种类繁多且可接受多种配体激活 2.下游基因激活可编辑 | 受限于GPCR的配体种类 |

| Syn-Notch[ | 1. 受体与配体结合特异性高 2.配体可选择范围广 3.可实现广泛性的目的基因表达 | 仅用于与细胞之间的配受体结合 |

| GEMS[ | 1. 配体可选择范围广 2.配体可选择为游离性配体 3. 天然信号通路,信号传导成功率高 4. 同源二聚体,工作效率与改造成功率高 5. 自激活概率低 | 信号传导局限于可选择的天然信号通路 |

| MESA[ | 1配体可选择范围广 2.配体可选择为游离性配体 3. 能够选择性表达目的产物 | 1. 异二聚体工作效率低 2. 多种质粒转染,细胞负担大 3. 有概率自激活 |

表1 经典工程化受体优缺点

Table 1 Advantages and disadvantages of classical engineered receptors

| 工程化受体 | 优点 | 缺点 |

|---|---|---|

| RASSL[ | 1.GPCR种类繁多且可接受多种配体激活 2.改造GPCR结合配体特异性高 | 1. 依赖于突变 2. 受限于GPCR的配体种类 3. 局限于GPCR自身激活的通路 |

| Tango[ | 1.GPCR种类繁多且可接受多种配体激活 2.下游基因激活可编辑 | 受限于GPCR的配体种类 |

| Syn-Notch[ | 1. 受体与配体结合特异性高 2.配体可选择范围广 3.可实现广泛性的目的基因表达 | 仅用于与细胞之间的配受体结合 |

| GEMS[ | 1. 配体可选择范围广 2.配体可选择为游离性配体 3. 天然信号通路,信号传导成功率高 4. 同源二聚体,工作效率与改造成功率高 5. 自激活概率低 | 信号传导局限于可选择的天然信号通路 |

| MESA[ | 1配体可选择范围广 2.配体可选择为游离性配体 3. 能够选择性表达目的产物 | 1. 异二聚体工作效率低 2. 多种质粒转染,细胞负担大 3. 有概率自激活 |

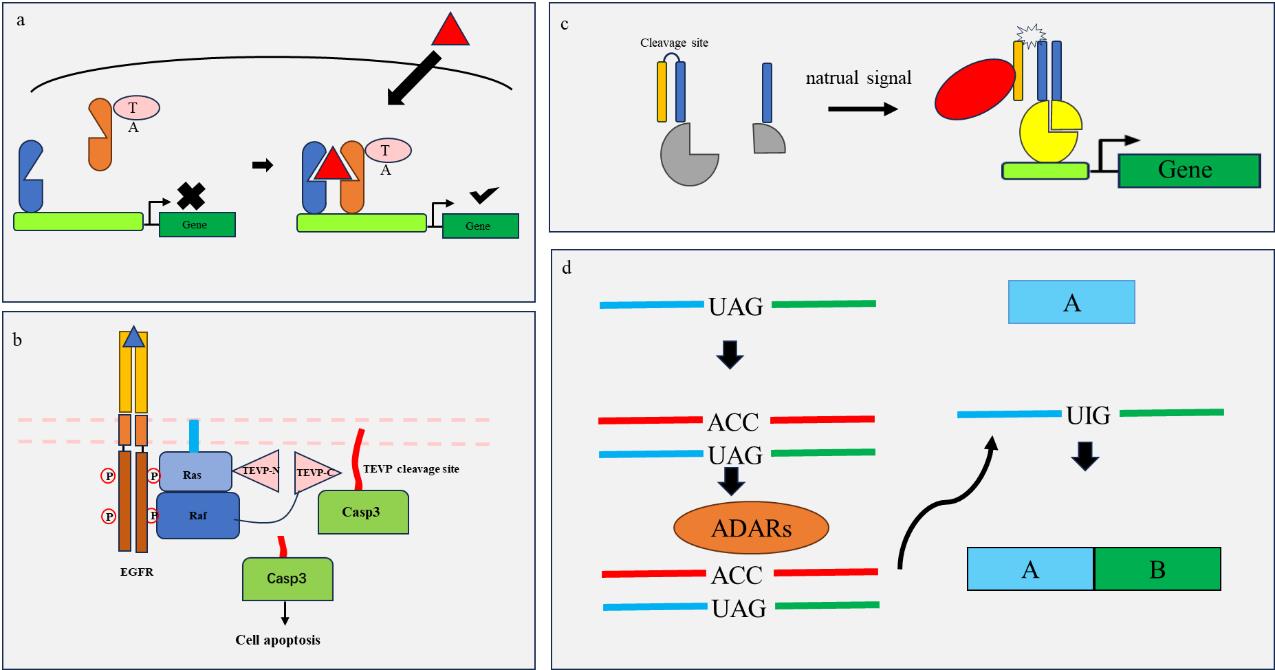

图2 工程化元件原理示意图(a) “HTH”转录因子依赖信号(红色)二聚化后,成为带有转录激活因子(TA)的完整转录因子,启动下游基因表达;(b)“CHOMP”系统利用Ras信号通路激活后Ras与Raf的结合,实现蛋白酶TEV组装切割caspase3,引起细胞凋亡;(c) “SPOC”逻辑利用内源信号激活胞内蛋白酶(红色)切割无用卷曲螺旋(橙黄色)与效应卷曲螺旋(蓝色)之间的酶切位点,携带效应子卷曲螺旋(蓝色)相互结合引起效应子激活(黄色),启动下游基因转录;(d)“DART VADAR”系统利用工程化RNA链(红色)靶向目的RNA(蓝色,绿色),错配段引发ADARs修复终止密码子,转录得以继续。

Fig. 2 Schematic diagram of engineering components principle(a) After dimerization of the "HTH" transcription factor dependent signal (red), it becomes a complete transcription factor with transcription activator (TA), initiating downstream gene expression; (b) The "CHOMP" system uses the Ras signaling pathway to activate the binding of Ras and Raf, achieving the assembly and cleavage of caspase 3 by protease TEV, causing cell apoptosis; (c) The "SPOC" logic utilizes endogenous signals to activate intracellular proteases (red) to cleave enzyme cleavage sites between useless coiled coils (orange yellow) and effector coiled coils (blue), carrying effector coiled coils (blue) to bind with each other, causing effector activation (yellow) and initiating downstream gene transcription; (d) The "DART VADAR" system uses engineered RNA strands (red) to target the target RNA (blue, green), and mismatches trigger ADARs to repair stop codons, allowing transcription to continue.

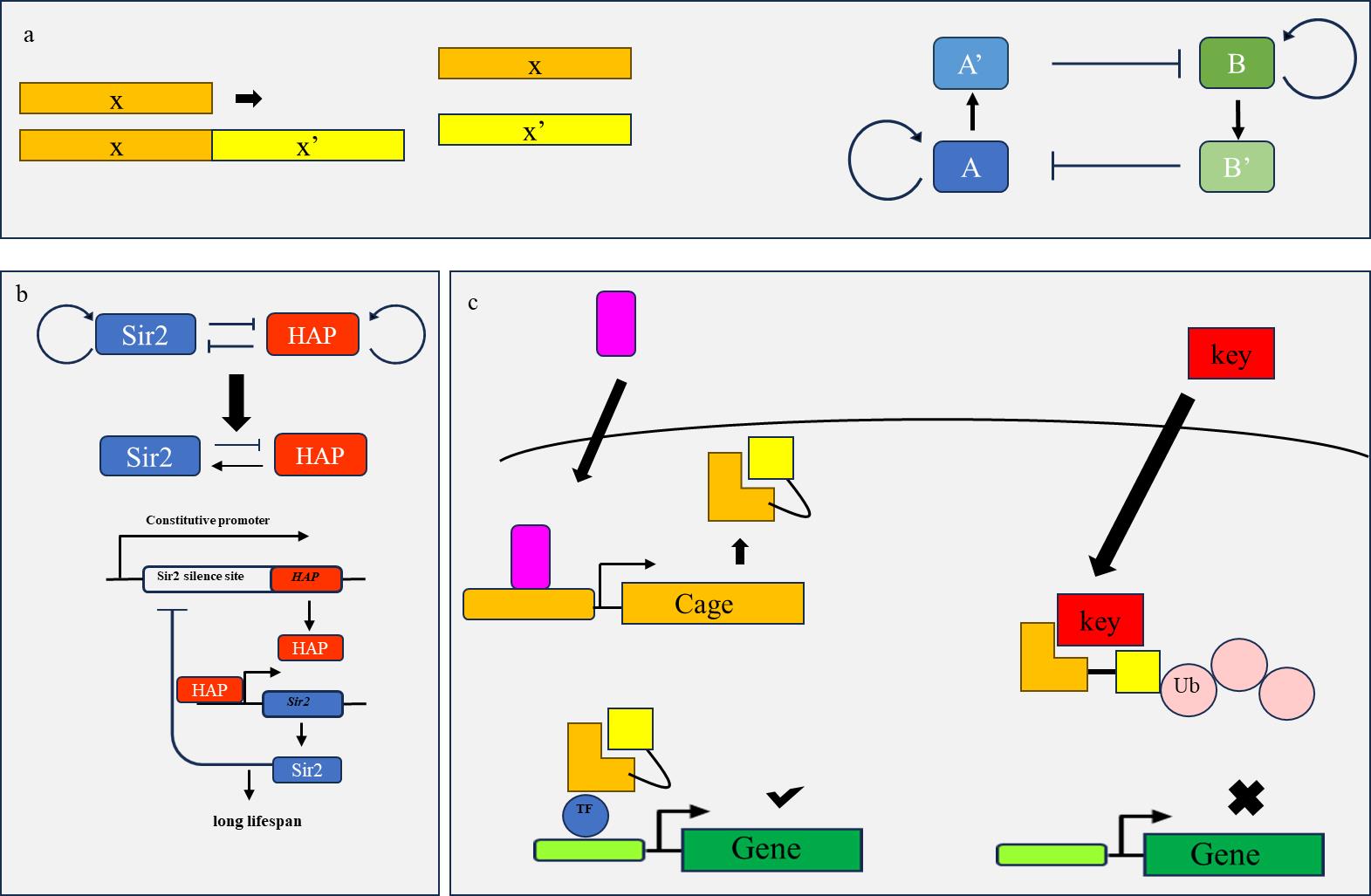

图3 工程化环路原理示意图(a) 双稳态系统中A,B两种核酸产物各自自激活与互相抑制,实现A,B两种状态的转变;(b)酵母中两种互相抑制的基因通过在其启动子与沉默位点下游改造实现整体负反馈调节,使得各自基因产物分开表达,实现细胞周期持续延长;(c) “LOCKR”系统利用KEY竞争性结合Cage使得Cage降解实现对Cage基因产物的控制,达到对调控Cage的信号(紫色)的耐受。

Fig. 3 Schematic diagram of engineering loop principle(a) In a bistable system, the two nucleic acid products A and B self-activate and mutually inhibit each other, achieving the transition between the two states of A and B; (b) Two mutually inhibitory genes in yeast achieve overall negative feedback regulation by downstream modification of their promoters and silencing sites, allowing their respective gene products to be expressed separately and achieving sustained cell cycle elongation; (c) The "LOCKR" system utilizes KEY competitive binding with Cage to control the degradation of Cage gene products, achieving tolerance to the signal (purple) that regulates Cage.

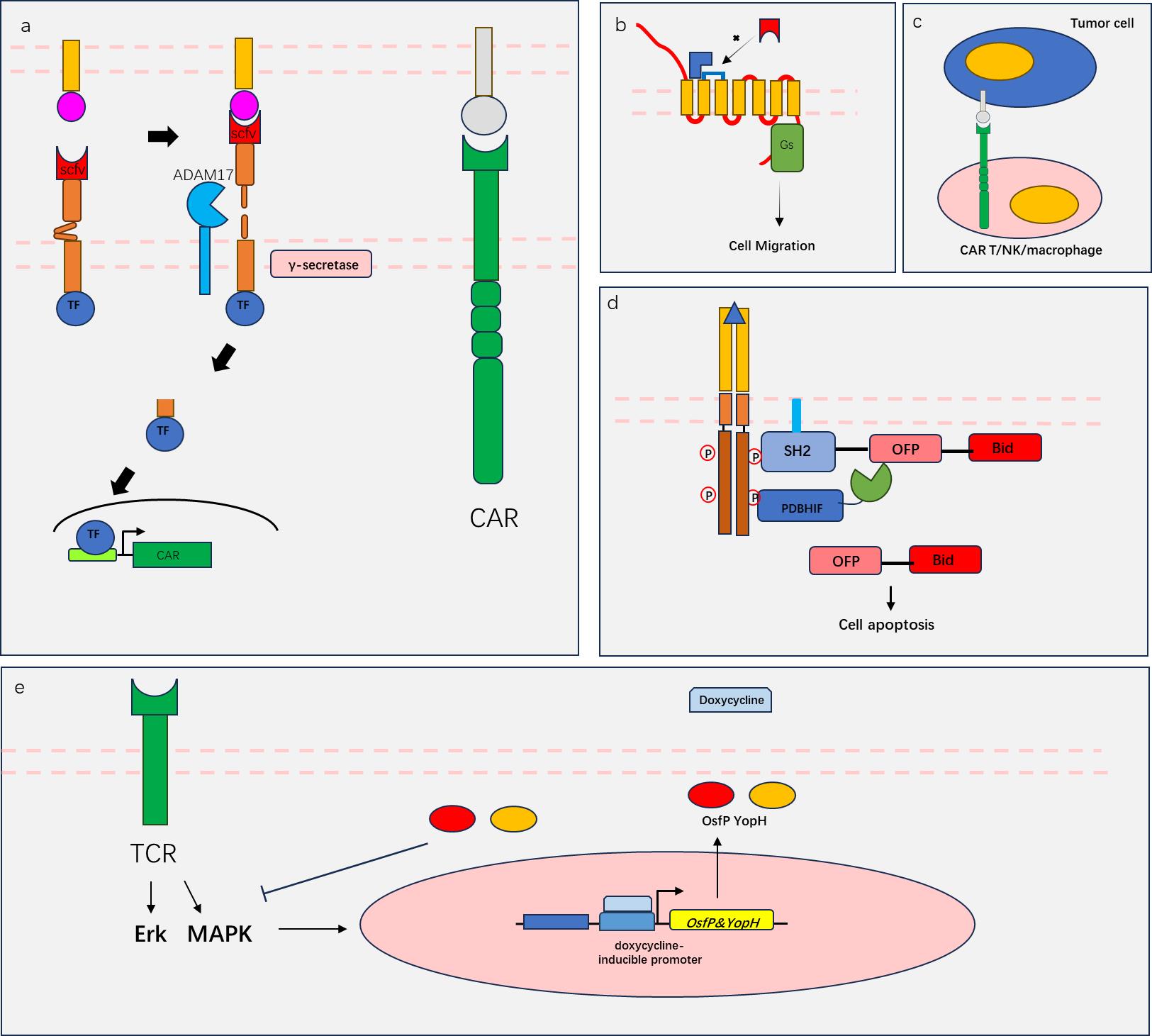

图4 合成生物学免疫治疗应用(a)syn-notch系统与CAR联合运用,肿瘤抗原一(红色)激活syn-notch促进CAR的表达,结合肿瘤抗原二(灰色),实现T细胞被肿瘤双抗原激活;(b)RASSL系统实现特定药物(蓝色)激活的细胞迁移信号;(c)CAR T/NK/macrophage示意图;(d)“RASER”系统示意图;(e) OspF 和YopH负反馈抑制TCR激活。(a) The syn notch system is used in combination with CAR. Tumor antigen one (red) activates syn notch to promote CAR expression, and when combined with tumor antigen two (gray), T cells are activated by tumor dual antigens; (b) RASSL system realizes cell migration signals activated by specific drugs (blue); (c) CAR T/NK/machophage schematic diagram; (d) RASER system schematic diagram; (e) OspF and YopH negative feedback inhibit TCR activation.

| CAR免疫细胞 | 优点 | 缺点 |

|---|---|---|

| CAR-T | 1.肿瘤杀伤强: T细胞具有多种肿瘤杀伤手段,能够分泌穿孔素、颗粒酶引发肿瘤细胞死亡,通过死亡受体途径(Fas/FasL)引发肿瘤细胞凋亡,通过大量细胞因子分泌增强自身,抑制及杀伤肿瘤[ 2.持久性强:T细胞 一旦激活,能够大规模扩增,并在体内形成长期免疫记忆,提供持续的监视和杀伤效果[ 3.杀伤效率高:T细胞杀伤肿瘤后并不会发生凋亡,可立即脱离寻找下一个肿瘤细胞[ 4.技术相对成熟: 是第一个成功商业化的细胞疗法,拥有大量的临床数据、生产工艺和经验[ | 1.毒副作用强:T细胞激活后细胞因子释放能力强,易造成细胞因子释放综合征[ 2.治疗实体瘤效果差: 肿瘤免疫微环境使得T细胞迁移进入肿瘤的信号不足,难以浸润实体瘤[ 3.自体来源为主: 目前多为自体疗法,导致制备成本高、时间长[ 4.可能脱靶:靶抗原在正常组织上也有低水平表达会导致T细胞攻击正常细胞[ |

| CAR-NK | 1.毒性低: NK细胞通过不同的机制杀伤靶细胞,不会引起严重的细胞因子释放[ 2.通用性高:不同于T细胞这类适应性免疫细胞,NK细胞作为固有免疫细胞 可以从健康供体的外周血、脐带血或NK细胞系扩增而来,有望成为通用型产品,成本更低[ 3.对实体瘤潜力更大: 具有更好的肿瘤组织浸润能力,且在肿瘤微环境中仍能保持一定的活性[ | 1.持久作用短: NK细胞在体内的存活时间较短,无法形成长期的免疫记忆[ 2.增殖能力有限: 在体内的增殖能力不如T细胞[ 3.技术尚不成熟: 实验数据与临床数据远少于CAR-T[ |

| CAR-M | 1.实体瘤浸润能力强: 巨噬细胞天生具有浸润到实体瘤深部的能力[ 2.具有重塑肿瘤微环境的能力: 活化的CAR-M不仅能直接杀伤肿瘤,还能分泌细胞因子(如IFN-γ)将抑制性的M2型巨噬细胞转化为杀伤性的“M1型”,并招募其他的免疫细胞(如T细胞)到肿瘤部位[ 3.吞噬作用: 能够通过强大的吞噬作用直接吞噬肿瘤细胞[ 4.通用性强:作为固有免疫细胞,可在体外大量扩增改造[ | 1.存在促瘤风险: 巨噬细胞如果功能失调,反而可能被肿瘤微环境刺激成为M2型巨噬细胞,加重肿瘤进展[ 2.肿瘤杀伤效率低:巨噬细胞随着吞噬肿瘤细胞数量增多,自身会发生凋亡,无法做到T细胞的持续杀伤[ 3.体内增殖能力差:相较于T细胞,体内活化后的巨噬细胞增殖能力差[ |

表2 不同CAR免疫细胞的比较

Table 2 Comparison of different CAR immune cells

| CAR免疫细胞 | 优点 | 缺点 |

|---|---|---|

| CAR-T | 1.肿瘤杀伤强: T细胞具有多种肿瘤杀伤手段,能够分泌穿孔素、颗粒酶引发肿瘤细胞死亡,通过死亡受体途径(Fas/FasL)引发肿瘤细胞凋亡,通过大量细胞因子分泌增强自身,抑制及杀伤肿瘤[ 2.持久性强:T细胞 一旦激活,能够大规模扩增,并在体内形成长期免疫记忆,提供持续的监视和杀伤效果[ 3.杀伤效率高:T细胞杀伤肿瘤后并不会发生凋亡,可立即脱离寻找下一个肿瘤细胞[ 4.技术相对成熟: 是第一个成功商业化的细胞疗法,拥有大量的临床数据、生产工艺和经验[ | 1.毒副作用强:T细胞激活后细胞因子释放能力强,易造成细胞因子释放综合征[ 2.治疗实体瘤效果差: 肿瘤免疫微环境使得T细胞迁移进入肿瘤的信号不足,难以浸润实体瘤[ 3.自体来源为主: 目前多为自体疗法,导致制备成本高、时间长[ 4.可能脱靶:靶抗原在正常组织上也有低水平表达会导致T细胞攻击正常细胞[ |

| CAR-NK | 1.毒性低: NK细胞通过不同的机制杀伤靶细胞,不会引起严重的细胞因子释放[ 2.通用性高:不同于T细胞这类适应性免疫细胞,NK细胞作为固有免疫细胞 可以从健康供体的外周血、脐带血或NK细胞系扩增而来,有望成为通用型产品,成本更低[ 3.对实体瘤潜力更大: 具有更好的肿瘤组织浸润能力,且在肿瘤微环境中仍能保持一定的活性[ | 1.持久作用短: NK细胞在体内的存活时间较短,无法形成长期的免疫记忆[ 2.增殖能力有限: 在体内的增殖能力不如T细胞[ 3.技术尚不成熟: 实验数据与临床数据远少于CAR-T[ |

| CAR-M | 1.实体瘤浸润能力强: 巨噬细胞天生具有浸润到实体瘤深部的能力[ 2.具有重塑肿瘤微环境的能力: 活化的CAR-M不仅能直接杀伤肿瘤,还能分泌细胞因子(如IFN-γ)将抑制性的M2型巨噬细胞转化为杀伤性的“M1型”,并招募其他的免疫细胞(如T细胞)到肿瘤部位[ 3.吞噬作用: 能够通过强大的吞噬作用直接吞噬肿瘤细胞[ 4.通用性强:作为固有免疫细胞,可在体外大量扩增改造[ | 1.存在促瘤风险: 巨噬细胞如果功能失调,反而可能被肿瘤微环境刺激成为M2型巨噬细胞,加重肿瘤进展[ 2.肿瘤杀伤效率低:巨噬细胞随着吞噬肿瘤细胞数量增多,自身会发生凋亡,无法做到T细胞的持续杀伤[ 3.体内增殖能力差:相较于T细胞,体内活化后的巨噬细胞增殖能力差[ |

| [1] | COUZIN-FRANKEL J. Cancer immunotherapy[J]. Science, 2013, 342(6165): 1432-1433. |

| [2] | RIEDEL S. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination[J]. Proceedings, 2005, 18(1): 21-25. |

| [3] | MCCARTHY E F. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft-tissue sarcomas[J]. The Iowa Orthopaedic Journal, 2006, 26: 154-158. |

| [4] | MANOHAR S, JHAVERI K D, PERAZELLA M A. Immunotherapy-related acute kidney injury[J]. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease, 2021, 28(5): 429-437.e1. |

| [5] | KENNEDY L B, SALAMA A K S. A review of cancer immunotherapy toxicity[J]. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2020, 70(2): 86-104. |

| [6] | YANG H X, YAO Z R, ZHOU X X, et al. Immune-related adverse events of checkpoint inhibitors: Insights into immunological dysregulation[J]. Clinical Immunology, 2020, 213: 108377. |

| [7] | MITRA A, BARUA A, HUANG L P, et al. From bench to bedside: the history and progress of CAR T cell therapy[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023, 14: 1188049. |

| [8] | TURTLE C J, HAY K A, HANAFI L A, et al. Durable molecular remissions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells after failure of ibrutinib[J]. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2017, 35(26): 3010-3020. |

| [9] | CAMERON D E, BASHOR C J, COLLINS J J. A brief history of synthetic biology[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2014, 12(5): 381-390. |

| [10] | YANG S, SLEIGHT S C, SAURO H M. Rationally designed bidirectional promoter improves the evolutionary stability of synthetic genetic circuits[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2013, 41(1): e33. |

| [11] | CHAPPELL J, WATTERS K E, TAKAHASHI M K, et al. A renaissance in RNA synthetic biology: new mechanisms, applications and tools for the future[J]. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 2015, 28: 47-56. |

| [12] | KHALIL A S, LU T K, BASHOR C J, et al. A synthetic biology framework for programming eukaryotic transcription functions[J]. Cell, 2012, 150(3): 647-658. |

| [13] | QUINN J Y, COX R S, ADLER A, et al. SBOL visual: a graphical language for genetic designs[J]. PLoS Biology, 2015, 13(12): e1002310. |

| [14] | MISHRA D, RIVERA P M, LIN A, et al. A load driver device for engineering modularity in biological networks[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2014, 32(12): 1268-1275. |

| [15] | GARDNER T S, CANTOR C R, COLLINS J J. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli [J]. Nature, 2000, 403(6767): 339-342. |

| [16] | LIU Y, HUANG Y X, LU R, et al. Synthetic biology applications of the yeast mating signal pathway[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2022, 40(5): 620-631. |

| [17] | RYU J, PARK S H. Simple synthetic protein scaffolds can create adjustable artificial MAPK circuits in yeast and mammalian cells[J]. Science Signaling, 2015, 8(383): ra66. |

| [18] | LI S Y, TANG H, LI C, et al. Synthetic biology technologies and genetically engineering strategies for enhanced cell therapeutics[J]. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 2023, 19(2): 309-321. |

| [19] | TRENTESAUX C, YAMADA T, KLEIN O D, et al. Harnessing synthetic biology to engineer organoids and tissues[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2023, 30(1): 10-19. |

| [20] | SOLÉ R V, MONTAÑEZ R, DURAN-NEBREDA S. Synthetic circuit designs for earth terraformation[J]. Biology Direct, 2015, 10(1): 37. |

| [21] | SHIH R M, CHEN Y Y. Engineering principles for synthetic biology circuits in cancer immunotherapy[J]. Cancer Immunology Research, 2022, 10(1): 6-11. |

| [22] | WEBER J S, YANG J C, ATKINS M B, et al. Toxicities of immunotherapy for the practitioner[J]. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2015, 33(18): 2092-2099. |

| [23] | THOMPSON J A. New NCCN guidelines: recognition and management of immunotherapy-related toxicity[J]. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2018, 16(5S): 594-596. |

| [24] | NEELAPU S S, TUMMALA S, KEBRIAEI P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy - assessment and management of toxicities[J]. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2018, 15(1): 47-62. |

| [25] | VAN ERP E A, VAN KAMPEN M R, VAN KASTEREN P B, et al. Viral infection of human natural killer cells[J]. Viruses, 2019, 11(3): 243. |

| [26] | LE BERT N, TAN A T, KUNASEGARAN K, et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls[J]. Nature, 2020, 584(7821): 457-462. |

| [27] | DARVIN P, TOOR S M, SASIDHARAN NAIR V, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers[J]. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 2018, 50(12): 1-11. |

| [28] | KEIR M E, BUTTE M J, FREEMAN G J, et al. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity[J]. Annual Review of Immunology, 2008, 26: 677-704. |

| [29] | CURRAN K J, PEGRAM H J, BRENTJENS R J. Chimeric antigen receptors for T cell immunotherapy: current understanding and future directions[J]. The Journal of Gene Medicine, 2012, 14(6): 405-415. |

| [30] | LINETTE G P, STADTMAUER E A, MAUS M V, et al. Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma[J]. Blood, 2013, 122(6): 863-871. |

| [31] | WAT J, BARMETTLER S. Hypogammaglobulinemia after chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy: characteristics, management, and future directions[J]. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: in Practice, 2022, 10(2): 460-466. |

| [32] | ARNETH B. Tumor microenvironment[J]. Medicina, 2020, 56(1): 15. |

| [33] | ZARETSKY J M, GARCIA-DIAZ A, SHIN D S, et al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2016, 375(9): 819-829. |

| [34] | SHIN D S, ZARETSKY J M, ESCUIN-ORDINAS H, et al. Primary resistance to PD-1 blockade mediated by JAK1/2 mutations[J]. Cancer Discovery, 2017, 7(2): 188-201. |

| [35] | SHAH N N, FRY T J. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy[J]. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2019, 16(6): 372-385. |

| [36] | SIEGLER E L, ZHU Y N, WANG P, et al. Off-the-shelf CAR-NK cells for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2018, 23(2): 160-161. |

| [37] | LIN J K, LERMAN B J, BARNES J I, et al. Cost effectiveness of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory pediatric B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2018, 36(32): 3192-3202. |

| [38] | DEPIL S, DUCHATEAU P, GRUPP S A, et al. 'Off-the-shelf' allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges[J]. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2020, 19(3): 185-199. |

| [39] | LIN H L, CHENG J L, MU W, et al. Advances in universal CAR-T cell therapy[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021, 12: 744823. |

| [40] | ENDY D. Foundations for engineering biology[J]. Nature, 2005, 438(7067): 449-453. |

| [41] | ANDRIANANTOANDRO E, BASU S, KARIG D K, et al. Synthetic biology: new engineering rules for an emerging discipline[J]. Molecular Systems Biology, 2006, 2: 2006.0028. |

| [42] | GROUP B F, BAKER D, CHURCH G, et al. Engineering life: building a fab for biology[J]. Scientific American, 2006, 294(6): 44-51. |

| [43] | THIEL G, KAUFMANN A, RÖSSLER O G. G-protein-coupled designer receptors - new chemical-genetic tools for signal transduction research[J]. Biological Chemistry, 2013, 394(12): 1615-1622. |

| [44] | CONKLIN B R, HSIAO E C, CLAEYSEN S, et al. Engineering GPCR signaling pathways with RASSLs[J]. Nature Methods, 2008, 5(8): 673-678. |

| [45] | MCCUDDEN C R, HAINS M D, KIMPLE R J, et al. G-protein signaling: back to the future[J]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2005, 62(5): 551-577. |

| [46] | WICKMAN K, CLAPHAM D E. Ion channel regulation by G proteins[J]. Physiological Reviews, 1995, 75(4): 865-885. |

| [47] | VAN BIESEN T, LUTTRELL L M, HAWES B E, et al. Mitogenic signaling via G protein-coupled receptors[J]. Endocrine Reviews, 1996, 17(6): 698-714. |

| [48] | SPIEGEL A M, SHENKER A, WEINSTEIN L S. Receptor-effector coupling by G proteins: implications for normal and abnormal signal transduction[J]. Endocrine Reviews, 1992, 13(3): 536-565. |

| [49] | COWARD P, WADA H G, FALK M S, et al. Controlling signaling with a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1998, 95(1): 352-357. |

| [50] | LEFKOWITZ R J, SHENOY S K. Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins[J]. Science, 2005, 308(5721): 512-517. |

| [51] | SHENOY S K, LEFKOWITZ R J. β-Arrestin-mediated receptor trafficking and signal transduction[J]. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 2011, 32(9): 521-533. |

| [52] | REITER E, AHN S, SHUKLA A K, et al. Molecular mechanism of β-arrestin-biased agonism at seven-transmembrane receptors[J]. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 2012, 52: 179-197. |

| [53] | BARNEA G, STRAPPS W, HERRADA G, et al. The genetic design of signaling cascades to record receptor activation[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(1): 64-69. |

| [54] | KIPNISS N H, DINGAL P C D P, ABBOTT T R, et al. Engineering cell sensing and responses using a GPCR-coupled CRISPR-Cas system[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 2212. |

| [55] | ANDERSSON E R, SANDBERG R, LENDAHL U. Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function[J]. Development, 2011, 138(17): 3593-3612. |

| [56] | WANG H F, ZANG C Z, LIU X S, et al. The role of Notch receptors in transcriptional regulation[J]. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2015, 230(5): 982-988. |

| [57] | GORDON W R, VARDAR-ULU D, HISTEN G, et al. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch[J]. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 2007, 14(4): 295-300. |

| [58] | GORDON W R, ZIMMERMAN B, HE L, et al. Mechanical allostery: evidence for a force requirement in the proteolytic activation of Notch[J]. Developmental Cell, 2015, 33(6): 729-736. |

| [59] | STRUHL G, ADACHI A. Nuclear access and action of Notch in vivo [J]. Cell, 1998, 93(4): 649-660. |

| [60] | MORSUT L, ROYBAL K T, XIONG X, et al. Engineering customized cell sensing and response behaviors using synthetic Notch receptors[J]. Cell, 2016, 164(4): 780-791. |

| [61] | MORAGA I, SPANGLER J, MENDOZA J L, et al. Multifarious determinants of cytokine receptor signaling specificity[J]. Advances in Immunology, 2014, 121: 1-39. |

| [62] | MORAGA I, WERNIG G, WILMES S, et al. Tuning cytokine receptor signaling by re-orienting dimer geometry with surrogate ligands[J]. Cell, 2015, 160(6): 1196-1208. |

| [63] | MORAGA I, SPANGLER J B, MENDOZA J L, et al. Synthekines are surrogate cytokine and growth factor agonists that compel signaling through non-natural receptor dimers[J]. eLife, 2017, 6: e22882. |

| [64] | REMY I, WILSON I A, MICHNICK S W. Erythropoietin receptor activation by a ligand-induced conformation change[J]. Science, 1999, 283(5404): 990-993. |

| [65] | CONSTANTINESCU S N, KEREN T, RUSS W P, et al. The erythropoietin receptor transmembrane domain mediates complex formation with viral anemic and polycythemic gp55 proteins[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2003, 278(44): 43755-43763. |

| [66] | WITTHUHN B A, QUELLE F W, SILVENNOINEN O, et al. JAK2 associates with the erythropoietin receptor and is tyrosine phosphorylated and activated following stimulation with erythropoietin[J]. Cell, 1993, 74(2): 227-236. |

| [67] | SCHELLER L, STRITTMATTER T, FUCHS D, et al. Generalized extracellular molecule sensor platform for programming cellular behavior[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2018, 14(7): 723-729. |

| [68] | DARINGER N M, DUDEK R M, SCHWARZ K A, et al. Modular extracellular sensor architecture for engineering mammalian cell-based devices[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2014, 3(12): 892-902. |

| [69] | HARTFIELD R M, SCHWARZ K A, MULDOON J J, et al. Multiplexing engineered receptors for multiparametric evaluation of environmental ligands[J]. ACS Synthetic Biology, 2017, 6(11): 2042-2055. |

| [70] | SCHWARZ K A, DARINGER N M, DOLBERG T B, et al. Rewiring human cellular input–output using modular extracellular sensors[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2017, 13(2): 202-209. |

| [71] | URBAN D J, ROTH B L. DREADDs (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs): chemogenetic tools with therapeutic utility[J]. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 2015, 55: 399-417. |

| [72] | TODA S, BLAUCH L R, TANG S K Y, et al. Programming self-organizing multicellular structures with synthetic cell-cell signaling[J]. Science, 2018, 361(6398): 156-162. |

| [73] | BURRILL D R, SILVER P A. Making cellular memories[J]. Cell, 2010, 140(1): 13-18. |

| [74] | BROPHY J A N, MAGALLON K J, DUAN L N, et al. Synthetic genetic circuits as a means of reprogramming plant roots[J]. Science, 2022, 377(6607): 747-751. |

| [75] | WAN X Y, VOLPETTI F, PETROVA E, et al. Cascaded amplifying circuits enable ultrasensitive cellular sensors for toxic metals[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2019, 15(5): 540-548. |

| [76] | WEINBERG B H, CHO J H, AGARWAL Y, et al. High-performance chemical- and light-inducible recombinases in mammalian cells and mice[J]. Nature Communications, 2019, 10: 4845. |

| [77] | POTVIN-TROTTIER L, LORD N D, VINNICOMBE G, et al. Synchronous long-term oscillations in a synthetic gene circuit[J]. Nature, 2016, 538(7626): 514-517. |

| [78] | BERTSCHI A, WANG P L, GALVAN S, et al. Combinatorial protein dimerization enables precise multi-input synthetic computations[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2023, 19(6): 767-777. |

| [79] | CARRINGTON J C, DOUGHERTY W G. A viral cleavage site cassette: identification of amino acid sequences required for tobacco etch virus polyprotein processing[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1988, 85(10): 3391-3395. |

| [80] | TÖZSÉR J, TROPEA J E, CHERRY S, et al. Comparison of the substrate specificity of two potyvirus proteases[J]. The FEBS Journal, 2005, 272(2): 514-523. |

| [81] | BARTENSCHLAGER R. The NS3/4A proteinase of the hepatitis C virus: unravelling structure and function of an unusual enzyme and a prime target for antiviral therapy[J]. Journal of Viral Hepatitis, 1999, 6(3): 165-181. |

| [82] | GAO X J, CHONG L S, KIM M S, et al. Programmable protein circuits in living cells[J]. Science, 2018, 361(6408): 1252-1258. |

| [83] | COX A D, FESIK S W, KIMMELMAN A C, et al. Drugging the undruggable RAS: mission possible?[J]. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 2014, 13(11): 828-851. |

| [84] | DOWNWARD J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy[J]. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2003, 3(1): 11-22. |

| [85] | FINK T, LONZARIĆ J, PRAZNIK A, et al. Design of fast proteolysis-based signaling and logic circuits in mammalian cells[J]. Nature Chemical Biology, 2019, 15(2): 115-122. |

| [86] | GAYET R V, ILIA K, RAZAVI S, et al. Autocatalytic base editing for RNA-responsive translational control[J]. Nature Communications, 2023, 14: 1339. |

| [87] | SNEPPEN K, KRISHNA S, SEMSEY S. Simplified models of biological networks[J]. Annual Review of Biophysics, 2010, 39: 43-59. |

| [88] | LIM W A, LEE C M, TANG C. Design principles of regulatory networks: searching for the molecular algorithms of the cell[J]. Molecular Cell, 2013, 49(2): 202-212. |

| [89] | INNISS M C, SILVER P A. Building synthetic memory[J]. Current Biology, 2013, 23(17): R812-R816. |

| [90] | FERRELL J E. Self-perpetuating states in signal transduction: positive feedback, double-negative feedback and bistability[J]. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2002, 14(2): 140-148. |

| [91] | PADIRAC A, FUJII T, RONDELEZ Y. Bottom-up construction of in vitro switchable memories[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(47): E3212-E3220. |

| [92] | GOODWIN B B C. Temporal Organization in Cells: A Dynamic Theory of Cellular Control Processes[M]. London: Academic Press, 1963. |

| [93] | ZHOU Z, LIU Y T, FENG Y S, et al. Engineering longevity-design of a synthetic gene oscillator to slow cellular aging[J]. Science, 2023, 380(6643): 376-381. |

| [94] | KHAMMASH M H. Perfect adaptation in biology[J]. Cell Systems, 2021, 12(6): 509-521. |

| [95] | LANGAN R A, BOYKEN S E, NG A H, et al. De novo design of bioactive protein switches[J]. Nature, 2019, 572(7768): 205-210. |

| [96] | QUIJANO-RUBIO A, YEH H W, PARK J, et al. De novo design of modular and tunable protein biosensors[J]. Nature, 2021, 591(7850): 482-487. |

| [97] | ZHENG X H, WU Y Q, BI J C, et al. The use of supercytokines, immunocytokines, engager cytokines, and other synthetic cytokines in immunotherapy[J]. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 2022, 19(2): 192-209. |

| [98] | VAZQUEZ-LOMBARDI R, LOETSCH C, ZINKL D, et al. Potent antitumour activity of interleukin-2-Fc fusion proteins requires Fc-mediated depletion of regulatory T-cells[J]. Nature Communications, 2017, 8: 15373. |

| [99] | DE LUCA R, SOLTERMANN A, PRETTO F, et al. Potency-matched dual cytokine-antibody fusion proteins for cancer therapy[J]. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 2017, 16(11): 2442-2451. |

| [100] | SEIF M, EINSELE H, LÖFFLER J. CAR T cells beyond cancer: hope for immunomodulatory therapy of infectious diseases[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2019, 10: 2711. |

| [101] | PRESTI E LO, DIELI F, MERAVIGLIA S. Tumor-infiltrating γδ T lymphocytes: pathogenic role, clinical significance, and differential programing in the tumor microenvironment[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2014, 5: 607. |

| [102] | TASIAN S K, GARDNER R A. CD19-redirected chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells: a promising immunotherapy for children and adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)[J]. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology, 2015, 6(5): 228-241. |

| [103] | PARK J S, RHAU B, HERMANN A, et al. Synthetic control of mammalian-cell motility by engineering chemotaxis to an orthogonal bioinert chemical signal[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(16): 5896-5901. |

| [104] | MAALEJ K M, MERHI M, INCHAKALODY V P, et al. CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances[J]. Molecular Cancer, 2023, 22(1): 20. |

| [105] | ALBELDA S M. CAR T cell therapy for patients with solid tumours: key lessons to learn and unlearn[J]. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2024, 21(1): 47-66. |

| [106] | BAI Z L, FENG B, MCCLORY S E, et al. Single-cell CAR T atlas reveals type 2 function in 8-year leukaemia remission[J]. Nature, 2024, 634(8034): 702-711. |

| [107] | BUI T A, MEI H Q, SANG R, et al. Advancements and challenges in developing in vivo CAR T cell therapies for cancer treatment[J]. eBioMedicine, 2024, 106: 105266. |

| [108] | XU J, LIU L, PARONE P, et al. In-vivo B-cell maturation antigen CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma[J]. Lancet, 2025, 406(10500): 228-231. |

| [109] | MOHAMMADI M, NAJAFI H, MOHAMMADI P. CAR T-cell therapy in renal cell carcinoma: opportunities, challenges, and new strategies to overcome[J]. Medical Oncology, 2025, 42(6): 179. |

| [110] | LIU E L, MARIN D, BANERJEE P, et al. Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2020, 382(6): 545-553. |

| [111] | MYERS J A, MILLER J S. Exploring the NK cell platform for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2021, 18(2): 85-100. |

| [112] | XIE G Z, DONG H, LIANG Y, et al. CAR-NK cells: a promising cellular immunotherapy for cancer[J]. eBioMedicine, 2020, 59: 102975. |

| [113] | KLICHINSKY M, RUELLA M, SHESTOVA O, et al. Human chimeric antigen receptor macrophages for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2020, 38(8): 947-953. |

| [114] | ZHANG W L, LIU L, SU H F, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor macrophage therapy for breast tumours mediated by targeting the tumour extracellular matrix[J]. British Journal of Cancer, 2019, 121(10): 837-845. |

| [115] | KHAWAR M B, SUN H B. CAR-NK cells: from natural basis to design for kill[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021, 12: 707542. |

| [116] | CHU J, DENG Y, BENSON D M, et al. CS1-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered natural killer cells enhance in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma[J]. Leukemia, 2014, 28(4): 917-927. |

| [117] | BOUTILIER A J, ELSAWA S F. Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(13): 6995. |

| [118] | CHUNG H K, ZOU X Z, BAJAR B T, et al. A compact synthetic pathway rewires cancer signaling to therapeutic effector release[J]. Science, 2019, 364(6439): eaat6982. |

| [119] | WEI P, WONG W W, PARK J S, et al. Bacterial virulence proteins as tools to rewire kinase pathways in yeast and immune cells[J]. Nature, 2012, 488(7411): 384-388. |

| [120] | MAUDE S L, LAETSCH T W, BUECHNER J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2018, 378(5): 439-448. |

| [121] | PAN Q Z, WENG D S, LIU J Y, et al. Phase 1 clinical trial to assess safety and efficacy of NY-ESO-1-specific TCR T cells in HLA-a 02: 01 patients with advanced soft tissue sarcoma[J]. Cell Reports Medicine, 2023, 4(8): 101133. |

| [122] | ALLA S S M, TEKURU Y, LOKESH M S, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) as a treatment for melanoma: a systematic review[J]. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 2025, 31(3): 481-487. |

| [123] | CHO J H, OKUMA A, SOFJAN K, et al. Engineering advanced logic and distributed computing in human CAR immune cells[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12: 792. |

| [124] | VAKULSKAS C A, DEVER D P, RETTIG G R, et al. A high-fidelity Cas9 mutant delivered as a ribonucleoprotein complex enables efficient gene editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells[J]. Nature Medicine, 2018, 24(8): 1216-1224. |

| [125] | LU J R, JIANG G. The journey of CAR-T therapy in hematological malignancies[J]. Molecular Cancer, 2022, 21(1): 194. |

| [126] | SHIN J E, RIESSELMAN A J, KOLLASCH A W, et al. Protein design and variant prediction using autoregressive generative models[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12: 2403. |

| [127] | MARCHISIO M A, STELLING J. Computational design of synthetic gene circuits with composable parts[J]. Bioinformatics, 2008, 24(17): 1903-1910. |

| [128] | HALD ALBERTSEN C, KULKARNI J A, WITZIGMANN D, et al. The role of lipid components in lipid nanoparticles for vaccines and gene therapy[J]. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 2022, 188: 114416. |

| [129] | ISSER A, LIVINGSTON N K, SCHNECK J P. Biomaterials to enhance antigen-specific T cell expansion for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Biomaterials, 2021, 268: 120584. |

| [1] | 宋开南, 张礼文, 王超, 田平芳, 李广悦, 潘国辉, 徐玉泉. 小分子生物农药及其生物合成研究进展[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1203-1223. |

| [2] | 于文文, 吕雪芹, 李兆丰, 刘龙. 植物合成生物学与母乳低聚糖生物制造[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 992-997. |

| [3] | 颜钊涛, 周鹏飞, 汪阳忠, 张鑫, 谢雯燕, 田晨菲, 王勇. 植物合成生物学:植物细胞大规模培养的新机遇[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1107-1125. |

| [4] | 孙扬, 陈立超, 石艳云, 王珂, 吕丹丹, 徐秀美, 张立新. 作物光合作用合成生物学的策略与展望[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1025-1040. |

| [5] | 赵欣雨, 盛琦, 刘开放, 刘佳, 刘立明. 天冬氨酸族饲用氨基酸微生物细胞工厂的创制[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1184-1202. |

| [6] | 何杨昱, 杨凯, 王玮琳, 黄茜, 丘梓樱, 宋涛, 何流赏, 姚金鑫, 甘露, 何玉池. 国际基因工程机器大赛中植物合成生物学主题的设计与实践[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1243-1254. |

| [7] | 张学博, 朱成姝, 陈睿雲, 金庆姿, 刘晓, 熊燕, 陈大明. 农业合成生物学:政策规划与产业发展协同推进[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1224-1242. |

| [8] | 刘婕, 郜钰, 马永硕, 尚轶. 合成生物学在农业中的进展及挑战[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 998-1024. |

| [9] | 郑雷, 郑棋腾, 张天骄, 段鲲, 张瑞福. 构建根际合成微生物菌群促进作物养分高效吸收利用[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1058-1071. |

| [10] | 李超, 张焕, 杨军, 王二涛. 固氮合成生物学研究进展[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1041-1057. |

| [11] | 魏家秀, 嵇佩云, 节庆雨, 黄秋燕, 叶浩, 戴俊彪. 植物人工染色体的构建与应用[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(5): 1093-1106. |

| [12] | 方馨仪, 孙丽超, 霍毅欣, 王颖, 岳海涛. 微生物合成高级醇的发展趋势与挑战[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(4): 873-898. |

| [13] | 朱欣悦, 陈恬恬, 邵恒煊, 唐曼玉, 华威, 程艳玲. 益生菌辅助防治恶性肿瘤的研究进展[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(4): 899-919. |

| [14] | 吴晓燕, 宋琪, 许睿, 丁陈君, 陈方, 郭勍, 张波. 合成生物学研发竞争态势对比分析[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(4): 940-955. |

| [15] | 张建康, 王文君, 郭洪菊, 白北辰, 张亚飞, 袁征, 李彦辉, 李航. 基于机器视觉的高通量微生物克隆挑选工作站研制及应用[J]. 合成生物学, 2025, 6(4): 956-971. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||